Gustav Holst, ‘The Planets’ – Schools’ Project

This resource is designed to help you and your class use Gustav Holst’s 'The Planets' suite in the classroom, encouraging children to work in a creative, hands-on way in order to understand and enjoy this repertoire, often performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

We’ve outlined the background to the piece and how to listen it. We’ve also included a creative project that shows you how to create your own version of the most famous section – Mars.

Please feel free to adapt the ideas below to suit the resources you have and the needs of your children.

You can download a print-friendly version of this project here: LPO KS2 resources:_Gustav Holst – The Planets

This resource is © copyright Rachel Leach, London 2017 (see About the Author section at the bottom of the article for more information).

Resources needed for this project:

- Classroom percussion instruments and/or any orchestral instruments your children might be learning (some of the task can easily be adapted to work with body percussion/voice)

- Paper and pens

- A recording of Holst’s ‘The Planets’.

Listen to our recording

Gustav Holst (1874–1934): The Planets (Op. 32)

Gustav Holst was a British composer living and working in London 100 years ago. He was a very interesting man fascinated by space, astrology, alternative faiths, meditation and vegetarianism – in many ways he was completely ahead of his time.

The Planets orchestral suite from 1918 describes seven planets in music but looks at their moods or characters rather than their scientific properties. Each one has a subtitle that further explains the character of the music.

Holst’s planets are:

- Mars, the Bringer of War

In 5 time (5 beats in a bar) throughout with three epic climaxes. This movement greatly inspired the original music of ‘Star Wars’ by John Williams - Venus, the Bringer of Peace

Serene and beautiful with many orchestral solos and gentle accompaniment - Mercury, the Winged Messenger

Flickering and flighty. Ideas dance around the orchestra pinned down only by some difficult jagged rhythms - Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity

The emotional centre of the suite with a very famous tune that has been set as a hymn and a rugby anthem! - Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age

Holst’s favourite. Two spooky chords alternating back and forth like plodding footsteps. Mysterious and gloomy - Uranus, the Magician

Brass and timpani herald the arrival of ‘The Magician’ before a skipping, jerky dance takes over – very much in the style of Dukas’ ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’ from 20 years earlier - Neptune, the Mystic

Back in 5 time, this piece has shimmery, watery sounds and a magical ending with off-stage female chorus fading away to silence.

Holst’s piece features an enormous orchestra with quadruple winds, 6 horns, large percussion section, celeste and organ. Despite Holst’s worries that it was too modern for the first audiences, it was an immediate hit and remains one of the most popular orchestral pieces of all time

Classroom activities – Listening task

Listening to music in the classroom can be difficult, but giving children a task to do as they listen can help them to focus.

1. Have a class discussion about the planets. Find out how many your pupils can name and what they know about them. Write their ideas on the board.

2. Explain that an English composer called Gustav Holst decided to make music to describe seven of the planets. Holst believed that each planet had a character.

3. Ask your children to draw out the following table (you might save time by doing this for them as a handout ahead of time):

…and make a list of their ‘characters’ in a random order on the board:

| Old Age | Mystic | Flying messenger | Peace | Joy | Magician | War |

4. Listen to an extract of each planet (you can use tracks 1–7 in the playlist above) and challenge your children to match the character to the planet.

5. When this is done, discuss their findings. When everyone has the correct list (below), listen to the beginning of each one again and ask the class to write a couple of words in the ‘music’ column to describe the music.

You could encourage them to think about the speed, dynamics (loud or quiet?) and shape (is it spiky, smooth?) as well as more general non-musical words like ‘aggressive’, ‘gentle’ etc. Here are some example answers:

Taking it further:

It might be fun to find out what everyone’s favourite ‘planet’ music was and play that one in full. To keep their attention, you could ask them to draw whatever comes to mind as they listen (maybe within a big circular ‘planet’ shape).

Creative project: Mars

This project is designed to be used over four lessons.

It is possible to break down many famous pieces to just three crucial ideas. Working with these ideas to create new pieces helps pupils understand them from the inside out as they compose using the exact same material as the original composer. Here’s how to do that with Mars.

Session 1 – ‘A’ section: 3 rhythmic ideas and a crescendo

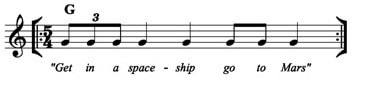

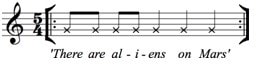

1. Stand your class in a circle and teach everyone the following rhythm:

Begin by encouraging your class to say the words over and over, to help them commit the rhythm to memory. Then demonstrate how to clap the pattern whilst whispering the words. Eventually take the words away and just think of them as you clap

Ask a volunteer to come forward and play the pattern on a percussion instrument of their choice (if they choose tuned percussion such as a xylophone, direct them towards the note G)

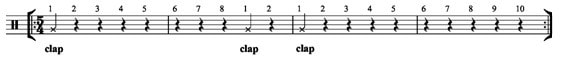

2. Next, practise counting to 8, 2 and 10 and clapping on number 1 of each count, like this:

The key to this is to count without leaving any gaps when you return to ‘1’

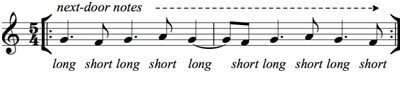

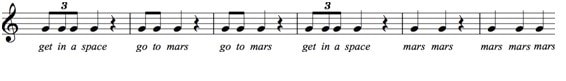

3. Finally demonstrate this uneven rhythm, again using the words to help keep everybody together.

If this rhythm is proving tricky, simply ask a volunteer to come forward and play an ‘uneven’ tune using ‘next-door (consecutive) notes.’

4. Split your circle into three groups, start each group on one of the above ideas and layer them up until all three rhythms are going at once.

5. Demonstrate how these patterns work on instruments:

- ‘get in a spaceship’ should be unpitched, or stick to one pitch – G

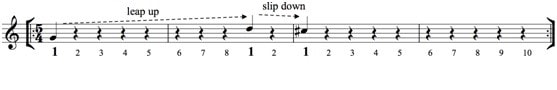

- 8, 2, 10 should leap up and then slip down as follows:

- the 3rd idea (the tune) moves only stepwise up and down from G (as above)

6. Look at your instrument collection and, as a class, decide on which instruments should play which element. It will be most effective if there are different instruments on each one.

i.e. get in a spaceship – just xylophones

8, 2, 10 – drums

tune – orchestral instruments

If you don’t have enough instruments, one team could use body percussion, such as clapping, or their voices.

7. Again, quickly split into three groups. Each group must create ONE of these elements on instruments.

8. Bring the class back together and try putting these patterns together to make the beginning of your piece. Discuss how you might order the ideas (Holst creates a crescendo, gradually getting louder) and how you will signal the ending.

Remember to write down what you’ve done for next time!

Session 2 – ‘B’ section: March

1. Holst creates a middle section for his music that is like a march. Demonstrate these three new ideas to the class as a warm-up.

(i) Steady pulse – clap a steady beat and encourage the class to join in until you make a big stop signal

(ii) Repeating rhythmic patterns (ostinatos)

Here’s a method for creating ostinatos:

- Ask your class a simple question such as ‘what is Mars like?’

- Ask your children to ‘think’ the answer over and over as you clap the pulse

- Now, ask them to speak their answer over your pulse

- And finally, ask them to clap the answer (clapping each syllable) round and around. This is an ostinato

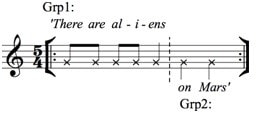

(iii) Holst splits his ostinatos between two or more players – the term for this is ‘hocketting’. Demonstrate this by choosing one of their ostinatos and teaching it to the class. For example:

Split this pattern in half and split the circle in half. Give each half of the circle, half of the pattern like this:

This is hocketting.

If you want to be really ‘Holstian’ challenge your children to invent ostinatos in 5!

2. Split the class into small working groups (two or four) and challenge them to create their own march using these three elements.

3. Listen to the group pieces and decide as a class how to combine them into one piece.

4. Decide on an ending for this section. Holst’s comes to an abrupt halt, and you could do that too by appointing a conductor to signal the ending

Again, write down what you have done!

Session 3 – Structure A-B-A

1. Begin this lesson by recapping what you have created so far – i.e. the opening 3-ideas crescendo (A) and the march (B)

2. Explain that Holst’s piece has three sections. His third is a combination of ideas from the A and B sections you have already made.

3. Challenge your class to create a third section. They could try to combine ideas from A and B or simply repeat the A section in full and thus create an ‘A-B-A’ (sandwich) shape. The technical term for this is Ternary Form – one of the most used shapes in music

4. End this session by practising your piece so far and perhaps make a big diagram of it on the board.

Session 4 – Coda (ending)

1. Holst’s piece ends with a short coda (coda just means ‘ending’). Listen to this section with your class (it’s the final track in the playlist above). As you listen, ask the children to draw or write down what they hear.

2. Listen a few times and create a big version on the board. Perhaps you have something like this:

- Short scurrying x2

- Long scurrying

- Random ‘bangs’

- Big, long note

3. Challenge your children to make a similar coda on their instruments.

- To make the ‘scurrying’ appoint a conductor and ask them to stand in front of the class and make a quick, wiggling gesture for the scurrying and a clear stop sign. The class can play whatever they like for the ‘scurrying’ as long as they stop abruptly and neatly on the conductor’s gesture.

- Big bangs – Holst cuts up his ‘get in a spaceship’ rhythm and re-orders it to create these ‘random’ bangs. His goes something like this:

Ask your class to create a new order for these words, and rhythms by using a similar method and practise playing this on a G

- Big, long note – you might need a conductor for this last, long note too. They need to do a big gesture for the start of the long bang (which could also be on a G) and a gesture for the stop.

4. Finally, add this coda on to the end of the piece you created last week. Perform your finished piece to another class.

You could spend a fifth session perfecting everything you’ve done, before your performance, if you wish.

Taking it further:

Holst’s other planets and your own

You can use the three-ideas method with all of Holst’s movements. Begin by listening to the music with your class and define what the three most important (or useable) ideas are. You might want to simplify things by just listening to the opening minute or a short section within.

Once you have agreed on the three ideas, work with them using the instruments and resources you have available to build up your own compositions.

Here’s a guide to what you might find useful as you listen:

Venus

- Two chords slowly alternating as if saying ‘calm down’

- Solos, conversations between instruments

- Magical, shimmering ending

Mercury

- Fast notes passed between instruments

- A jagged rhythm

- iii. Dance with um-pa accompaniment

Jupiter

- 3-note upward pattern (sounds like laughter)

- Strident section with heavy bass

- Big, famous tune (put words to it!)

Saturn

- Plodding footsteps – two chords alternating

- solos

- grows to climax and then fades away

Uranus

- Four big brass notes echoed at different speeds “The Ma-gi-cian!”

- Uneven, jerky rhythm

- iii. Dance with upside down um-pa (i.e. ‘pa’ is stronger than ‘um’)

Neptune

- Soft parallel tune (in 5)

- Shimmery, watery sounds

- The off-stage wordless singing

Earth and Pluto

Holst didn’t make musical movements for Earth or Pluto (which wasn’t discovered until many years after his piece was written, and now has been downgraded to ‘dwarf-planet’ status). To make your own version of Earth or Pluto, simply ask your class, working in groups, to define the three most important facts about that planet, be they scientific facts or descriptions of life on that planet (e.g. for Earth they could have a scientific fact, like the fact that it is 71% water, or describe life here, for example that there are busy cities full of traffic).

When three ideas have been chosen, make a musical motif for each idea – keep these short – and then structure these ideas into a larger piece just as Holst did with Mars.

Throughout this much freer task, encourage your students to think clearly about structure and the development of ideas, rather than constantly creating new ideas. Remind them that very often Holst sets up his ideas at the very beginning of his music and then works with these ideas until the end, rather than baffling the listener with new sounds throughout.

In 2000, composer Colin Matthews wrote a piece called Pluto, the Renewer, as a companion piece to Holst’s Planets, which you may wish to play for your class. He composed it so that Holst’s Neptune would lead straight into his Pluto, completing the ‘Planets’ cycle. It is performed less nowadays, after Pluto’s declassification as a full planet.

About the author

Rachel Leach is one of the UK’s leading composers and animateurs. For 20 years she has been devising and leading education projects with the UK’s top orchestras and opera companies, delivering creative projects to a huge range of people across London, the UK and the world. She regularly presents BrightSparks schools concerts for the LPO and is the creative mentor on our flagship KS2 project: Creative Classrooms. www.rachelleachmusic.com/

Join the BrightSparks mailing list

To find out when BrightSparks concerts go on sale, and how you can book your class, join our mailing list.

Join mailing list

Back

Back